The Catholic Yijing: Lü Liben’s Passion Narratives in the Context of the Qing Prohibition of Christianity

1. Introduction: The Yijing-Figurism

2. The Figurist Remnant: Lü Liben and the Yijing benzhji

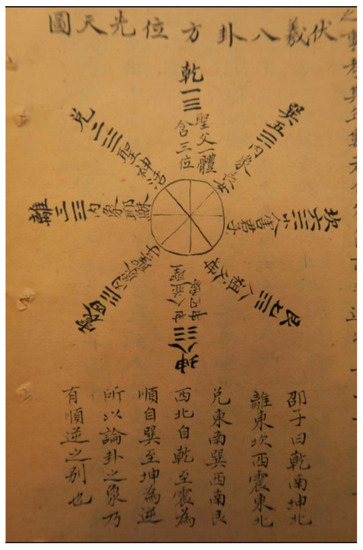

With limited biographical information about Lü Liben, the prologue sheds light on his interpretative approach of the Yijing. Lü proclaims that the Yijing “is an ancient scripture with hidden mysteries, and the very first holy scripture since the beginning of history.”13 In the subsequent section of Xici zhuan 繫辭傳 (The Great Treaties), which states that “Thus the Yijing consists of the images; the images are reproductions (是故易者象也,象也者像也),”14 Lü maintains that the Yi images originated from divine inspiration to reveal the mysteries of Christian salvation. Unfortunately, owing to later generations’ misinterpretations, the truth has been concealed. Lü did not hesitate to make his severe critique:

The original meaning of the Yijing consists of images, depicting the Logos, the true Lord coming down to Earth to save humankind. But because of Wang Bi’s approach of “sweeping away the images,” the truth has been lost. […] Furthermore, there are fools who only bluff about false images without entity, deceiving people through divination to make money. Alas, they are so deluded! They have been committing cardinal sins, all because of their failure to understand the original meaning of the Yijing, and hence their descent into heresy and evil.15

3. ☵ Kan: The Toiling Savior of Modesty and Merit

4. ☶ Gen: The Gradual Progress to Mount Calvary

5. ☲ Li: The Yin-yang King on the Cross

At first glance, Lü’s numerical interpretative approach may seem unorthodox, if not heretical. The underlying assumption behind the development of his ideas, however, echoes largely with Shao Yong 邵雍 (1011–1077)’s Image-Number study. The famed Yijing scholar believed that numbers in the Yijing were far from meaningless. Thus, to discover some possible hidden meaning of the text, we must take into account the numerical representations. As he stated in Huangji jingshi shu 皇極經世書 (Supreme Principles for Governing the World):

If there are ideas, there must be words. If there are words, there must be images. If there are images, there must be numbers. After the numbers were established, then the images were produced. After the images were produced, then the words were clear. After the words were clear, then the ideas were manifest.54

Lü first utilizes numbers as a unique starting point for an imaginary reconstruction of the entire scene of Christ’s Passion. Then, step by step, he reproduces the biblical accounts with the use of trigrammatic images, and further expounds the text in the light of Catholic doctrine. Here in his exegesis of Li, Christ in the Passion is featured as the Savior who brings justice to the world. Instead of underscoring His suffering, Lü highlights the divine power Christ, who came to liberate man from the shackles of sin and death.55 It is worth mentioning that his interpretation resembles the distinctive symbol of the Jesuit Order: a flaming sun with the monogram IHS—the first three letters of Jesus’s name in Greek (IHΣOΥΣ)—which is surmounted by a cross and subtended by three nails. In both cases, Christ in the Passion is symbolized as the sun that brings light to the world.

Lü Liben strives to guide his readers to view Jesus as the archetypal martyr and the perfect example for all Catholic believers. He elaborates this point by explicating “His loud cries are as dissolving as sweat. Dissolution! A king abides without blame (渙汗其大號,渙王居,無咎)” and “‘A king abides without blame.’ He is in his proper place (王居無咎,正位也),” the statement and Xiaoxiang zhuan attached to line 5 of Huan 渙 ䷺ (Dispersion):

‘Dissolving [his] sweat’ originally indicates our Lord shedding His sweat and blood on behalf of sinners. This sets an example for all missionaries that one shall shed its sweat and blood as our Lord did. […] Our Lord’s body is the holy temple for the Trinity; yet he reconciled to give it up for us. I shall die in His name as if I was in my proper place. Jesus is my teacher while I am His disciple. How could I call myself His disciple if I did not follow His example?58

It is important to inquire the reason behind Lü’s strong declaration. Viewing the text through the lens of its context may offer some insight into Lü’s intentions. After the 1724 decree, only a few foreign missionaries had managed to stay or enter the Shanxi province.59 Since their distinctive appearance made them easy to be tracked down by local officials, they usually hid in the houses of their native converts in daytime and went out to perform their ministerial duties until very late at night. As a result, many of the pastoral responsibilities were shifted to the local Chinese Catholics.60 Putting their own lives at risk, they protected the foreign missionaries and found ways to preserve and preach on the doctrines. Some of them were arrested or even banished to die in exile.61 Evidently, it is not an exaggeration to claim that one shall shed his sweat and blood for the sake of Christ. Under the imminent threat of religious persecution, Lü utilizes the Yijing—the most practical and disguising instrument for Chinese Catholic communities to remember the sacred event of crucifixion that lays the Catholic foundation—to reaffirm their religious identity by bearing witness to the wounds of Christ who reveals his vulnerability, his inner being, and his incarnation.62 More importantly, in Lü’s exegesis, Christ in the Passion serves as a powerful symbol of unflinching faith and steadfast hope. By means of the example of Christ, Lü may inspire the faith communities that the affliction they were experiencing is merely transient, that the honor and glory would be eternal.

6. ☴ Xun: The Tree of Life and the Queen of Martyrs

As the mother of Jesus Christ, Virgin Mary played a prominent role in Lü Liben’s Passion narratives. Notably, in the Jian hexagram, Lü positions Mary at the very center of the crucifixion event and narrates the story from her point of view. As discussed earlier, Lü interprets that the hexagram evokes an image of Jesus on his way to Mount Calvary. In Lü’s depiction of the scene, Mary was single-heartedly accompanying her son along the Via Dolorosa, manifesting the depths of her sorrow and suffering:

Our Lord encountered His Mother on his way, and in His will he said, “Why do you follow me to this squalid place to deepen my pain? You shall return home.” [...] Ascending the Mount Calvary, all the bitter sufferings were at hand, her heart torn as if a knife had plunged and wrenched in it. Had it not been for the Lord’s grace, her life would not have been preserved. Our Lady was in great distress—all because of mankind’s sin.63

The imagery, in Lü’s view, is encapsulated by the upper trigram Xun ☴, with the judgement to the hexagram Jian saying, “Development. The maiden is given in marriage. Good fortune. Perseverance further (漸,女歸吉,利貞).” In Lü’s own symbolism, Xun, the Eldest Daughter, is used to signify Virgin Mary in her relations with the trigram Li ☲. According to Lü, when line 1 of Xun exchanges its position with line 2, the trigram Li (signifying Christ) is formed. Lü claims that line 1 (yin) and line 2 (yang) of Xun represent respectively the human nature and the divinity of the Holy Son; and therefore, the transposition of these two lines symbolizes the unity of Christ’s humanity and divinity in the womb of the Virgin. Furthermore, Lü literally interprets gui 歸 as guijia 歸家 (return home), which captures two meanings: “the return of Mary” and “the repentance of sinners.” For the former, Lü argues that Mary could have chosen to return home and not to witness her son’s suffering; but instead, she opted to endure the pain for the sake of all humankind. Mary has further been portrayed not as a spectator, but as an indispensable participant in Christ’s Passion.

More remarkably, the Figurist Lü goes further to put Mary on the Cross. Discussing the hexagrammatic image, he applies the image of “tree on the mountain (山上有木)” to the Cross and the Virgin. In his reading, the Cross is denoted as the tree on Calvary while the Virgin is portrayed as the “Tree of Life (常生之樹),” which bears the “Fruit of Life (常生之菓),” Jesus Christ. The multi-layered symbolic meanings of Xun allow Lü to reiterate the obedience of the Cross (necessary for Christ’s death) in an attempt to recall the obedience of the Virgin (necessary for Christ’s birth). It is noteworthy that Lü’s portrayal of Mary bears a strong resemblance to Sirach 24:22–25, part of the Hebrew wisdom text that is applied to the Virgin in the traditional Roman Breviary.64 In the scripture the personified wisdom says:

I have stretched out my branches as the turpentine tree, and my branches are of honour and grace. As the vine I have brought forth a pleasant odour: and my flowers are the fruit of honour and riches. I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope. In me is all grace of the way and of the truth, in me is all hope of life and of virtue.65(我如得肋賓多樹展枝,我枝是榮寵的。我如葡萄樹開奇香花,此花使人得榮富。我是正愛、敬畏、大通、誠望之母。惟我能賞人行正路,明正道,盻加神力得常生。)66

Here in the biblical metaphor, Mary has been depicted as a tree of honor and grace, and as a mother given to all believers to bring forth virtue in them, and to lead them in the path to truth and life. Lü presents similar Marian images in his commentary. In his exegesis of Kun坤 ䷁, Mary is titled as “the Queen Mother of Heaven and Earth” (Tiandi zhi Muhuang 天地之母皇) and “the Patron of the whole World” (Pushi zhi zhubao 普世之主保), who “takes charge of everything important on Earth and was taken up into Heaven by grace.”67 The honorific titles are almost identical as those found in the early-Qing Daoist text Lidai shenxian tongjian 歷代神仙通鑑 (Comprehensive Accounts on the Immortals through the Dynasties, 1700), in which Mary (Maliya 瑪利亞) is presented as “Queen Mother of Heaven and Earth” (Tiandi zhi Muhuang 天地之母皇) and “Patron of All Peoples in the World” (Shiren zhi zhubao 世人之主保). While Lidai shenxian tongjian positions Mary as one of the Daoist immortals in the supernatural world,68 Lü reinterprets Mary as an ideal model of Confucian morality from the perspective of the Yijing discourse. Illustrating “Thus the superior man who has breadth of character carries the outer world (君子以厚德載物),” the commentary of the image attached to the hexagram Kun, Lü characterizes the Virgin as the “superior woman” (nüzhong junzi 女中君子) who takes up a heavy responsibility of the guardian of morality for all humankind. Furthermore, he foregrounds modesty as the exemplary virtue of Mary. In the section of line 3, Lü, by adopting the principle of changing lines (bianyao 變爻), points out that Kun would become Qian ䷎ when line 3 changes from yin to yang. In that event, the solid line 3 conveys the meaning of laoqian 勞謙. Lü acclaims Mary as the “laoqian junzi 勞謙君子” who gave virgin birth to Christ while retaining her modesty and humility. As discussed in the previous section regarding Lü’s exegesis of the Qian hexagram, Jesus Christ has similarly been venerated as the laoqian junzi for his toil and merit in completing the salvation work through the Passion. Apparently the Figurist intends to demonstrate the extent to which Mary may parallel Christ in her contribution to the accomplishment of the salvation.

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Aleni, Giulio. 2002. Kouduo richao 口鐸日抄 [Diary of Oral Admonitions]. In Yesuhui Luoma Dang’anguan Ming-Qing Tianzhujiao wenxian 耶穌會羅馬檔案館明清天主教文獻 [Chinese Christian Texts from the Roman Archives of the Society of Jesus]. Edited by Nicolas Standaert and Adrian Dudink. Taipei: Taipei Ricci Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, John. 2006. The Mystery of Christ: Life in Death. Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birdwhistell, Anne D. 1989. Transition to Neo-Confucianism: Shao Yung on Knowledge and Symbols of Reality. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catta, Etienne. 1961. Sedes Sapientiae. In Maria: études sur la Sainte Vierge. Edited by Hubert Du Manoir de Juaye. Paris: Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- Chardon, Louis. 1957. The Cross of Jesus. Translated by Richard Murphy, and Josefa Thornton. St. Louis: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xinyu 陳欣雨. 2017. Baijin Yixue sixiang yanjiu: Yi Fandigang tushuguan jiancun zhongwen Yixue shuju wei jichu 白晉易學思想研究—以梵蒂岡圖書館見存中文易學數據為基礎 [A Study of Bouvet’s Thought on the Yijing on the Basis of Relevant Materials in Chinese Collected in the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana]. Beijing: Renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yi 程頤. 2011. Zhouyi Cheng shi zhuan 周易程氏傳 [Cheng’s Commentary on the Zhouyi]. Collated by Wang Xiaoyu 王孝魚. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Hao 程顥, and Yi Cheng 程頤. 2006. Er Cheng ji 二程集 [Collected Writings of the Two Chengs]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Anthony E. 2011. China’s Saints: Catholic Martyrdom during the Qing (1644–1911). Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cullmann, Oscar. 1963. The Christology of the New Testament. Translated by Shirley C. Guthrie, and Charles A. M. Hall. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Poirot, Louis 賀清泰. 2014. Guxin shengjing cangao 古新聖經殘稿 [An Incomplete Manuscript of Poirot’s Chinese Bible]. Edited by Li Sher-shiueh 李奭學 and Zheng Haijuan 鄭海娟. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Durrwell, François-Xavier. 1969. The Resurrection: A Biblical Study. New York: Sheed and Ward. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Hao 方豪. 1943. Shiqiba shiji laihua xiren dui woguo jingji shi yanjiu 十七八世紀來華西人對我國經籍之研究 [The Foreigners’ Study of Chinese Classics in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century]. Shixiang yu shidai 19: 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Glotin, Edouard. 1979. Catechetical Value of a Symbolic Sign: The Wounded Heart of Jesus Christ. Rome: International Institute of the Heart of Jesus. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Weimin 顧衛民. 2000. Zhongguo yu luoma jiaoting guanxi shi 中國與羅馬教廷關係史 [A History of the Relations between China and the See of Rome]. Beijing: Dongfang chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Guardini, Romano. 1964. The Humanity of Christ: Contributions to a Psychology of Jesus. New York: Burns & Oates. [Google Scholar]

- David Hinton, trans. 2015, Tao Te Ching. Berkeley: Counterpoint.

- King James Bible. 1996. Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey.

- Lai, Zhide 來知德. 2013. Zhouyi jizhu 周易集註 [Collected Annotations on the Zhouyi]. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, James. 1861. The Doctrine of the Mean. In The Chinese Classics. Hong Kong: The Author. [Google Scholar]

- James Legge, trans. 1963, The I Ching, or Book of Changes. New York: Dover Publications.

- Li, Xueqin 李學勤, ed. 2000. Zhouyi zhengyi 周易正義 [The True Meaning of the Zhouyi]. In Shisanjing zhushu zhengli ben 十三經注疏 (整理本) [Commentaries and Subcommentaries on the Thirteen Confucian Classics (Collated Edition)]. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Guangdi 李光地. 2002. Zhouyi zhezhong 周易折中 [Balanced Annotations on the Zhouyi]. Annotated by Li Yixin 李一忻. Beijing: Jiuzhou chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Dingzuo 李鼎祚. 2016. Zhouyi jijie 周易集解 [Collected Explanations on the Zhouyi]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Anrong 劉安榮. 2017. Zhongguohua shiye xia Shanxi tianzhujiao shi yanjiu (1620–1949) 中國化視野下山西天主教史研究 (1620–1949) [The Study of the History of Shanxi Catholicism in the View of Sinolization (1620–1949)]. Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Liben 呂立本. 2013. Yijing benzhi 易經本旨 [Original Meaning of the Yijing]. In Xujiahui cangshulou Ming Qing Tianzhujiao wenxian xubian 徐家匯藏書樓明清天主教文獻續編 [The Sequel to the Chinese Christian Texts from the Zikawei Library]. Edited by Nicolas Standaert, Adrian Dudink and Wang Renfang. Taipei: Taipei Ricci Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk, Knud. 1991. Joseph de Prémare (1666–1736), S. J.: Chinese Philology and Figurism. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Lida 羅麗達. 1997. Baijin yanjiu Yijing shishi jikao 白晉研究《易經》史事稽考 [Historical Examination of Bouvet’s Yijing Studies]. Sinology Research (Taiwan) 15: 173–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mangenot, Eugene. 1924. Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. Paris: Librairie Letouzey et Ané. [Google Scholar]

- Mungello, David E. 1989. Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. First published in 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pius-Raymond. 1954. The Cross and the Christian. Translated by Angeline Bouchard. St. Louis: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzinger, Joseph. 1983. Daughter Zion: Meditations on the Church’s Marian Belief. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Giovanni. 1929. Vicariatus Taiyuanfu: seu Brevis historia antiquae Franciscanae missionis Shansi et Shensi a sua origine ad dies nostros (1700–1928). Pekini: Congregationis Missionis. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Alan. 1958. An Introduction to the Theology of the New Testament. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Rule, Paul A. 1986. K’ung-tzu or Confucius? The Jesuit Interpretation of Confucianism. Sydney: London: Boston: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Sava, Anthony. F. 1954. The Wounds of Christ. Catholic Biblical Quarterly 16: 438–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schottenhammer, Angela. 2007. The East Asian Maritime World 1400–1800: Its Fabrics of Power and Dynamics of Exchanges. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Gang. 2018. The Many Faces of Our Lady: Chinese Encounters with the Virgin Mary between 7th and 17th century. Monumenta Serica 66: 341–4. [Google Scholar]

- Standaert, Nicolas. 2001. Handbook of Christianity in China, Volume One: 635-1800. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- von Collani, Claudia. 1985. P. Joachim Bouvet S. J. Sein Leben und sein Werk. Nettetal: Steyler Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- von Collani, Claudia. 2007. The First Encounter of the West with the Yijing: Introduction to and Edition of Letters and Latin Translations by French Jesuits from the 18th Century. Monumenta Serica 55: 227–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Wilhelm, trans. 1967, The I Ching, or Book of Changes. Translated from German by Cary Baynes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Witek, John W. 1982. Controversial Ideas in China and in Europe: A Biography of Jean-François Foucquet, S.J., (1665–1741). Roma: Institutum Historicum S.I. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Qinghe 肖清和. 2015. Tianhiu yu wudang: Mingmo Qingchu Tianshujiaotu qunti yanjiu 「天會」與「吾黨」:明末清初天主教徒群體研究 [“Tianhu” and “Wudang”: A Study on Catholic Convert Groups in Late Ming and Early Qing]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiping 張西平. 1978. Ouzhou zaoqi hanxueshi zhongxi wenhua jiaoliu yu xifang hanxue de xingqi 歐洲早期漢學史—中西文化交流與西方漢學的興起 [A History of Early Sinology in Europe: Chinese-Western Cultural Exchange and the Rise of Western Sinology]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiping 張西平. 2005. Yijing yanjiu: Kangxi he faguo chuanjiaoshi baijin de wenhua diuhua 《易經》研究:康熙和法國傳教士白晉的文化對話 [The Study of Yijing: The Cultural Dialogue between the Kangxi Emperor and French Missionary Bouvet]. Wenhua zazhi 54: 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Li 張力, and Jiantang Liu 劉鑒唐. 1987. Zhongguo jiao’an shi 中國教案史 [A History of China’s Religious Court Cases]. Chengdu: Sichuan sheng shehui kexueyuan chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Peicheng 趙培成, Ruyang Wang 王如陽, and Yuanping Jin 晉原平. 1993. Xinzhou diqu zongjiao zhi 忻州地區宗教志 [Xinzhou District Religion Gazetteer]. Taiyuan: Shanxi renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi 朱熹. 2018. Zhouyi benyi 周易本義 [Original Meaning of the Zhouyi]. Annotated by Su Yong. Beijing: Peking University Press. First published in 2009.

| 1 | 易學索隱思想因在歐洲總體上受到教廷傳教總部的壓制,著作無法在歐洲出版發行,其思想也只能為少數人知曉,且在中國關於索隱派的易學著作亦從未刊行發表,故尚未發現有古代中國文人對其進行評價和研究。(Chen 2017, p. 333). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Previous studies have examined such issues as the intellectual background of Figurism, the life and works of Figurists. See (von Collani 1985; Witek 1982; Rule 1986; Lundbæk 1991; Zhang 1978, pp. 514–98). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | For the relationship between the Kangxi Emperor and Bouvet’s study of the Yijing, see (Fang 1943; Luo 1997; Zhang 2005). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Ibid., 237. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | 《易》乃古經隱義而為開闢以來第一聖經也。 (Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 3). The English translations of the Yijing Benzhi 易經本旨 (original meaning of the Yijing) are by the authors. |

| 14 | Unless otherwise specified, all English translations of the Yijing are from the Richard Wilhelm and Cary F. Baynes’s version. See (Wilhelm 1967). |

| 15 | 《易經》本旨有像,乃真道真主降世救人之像也,乃因王弼掃象而失其本來之像也[…]且有一種愚者只論其無實形之虛像,而以卜算命為事,以騙愚民錢財,迷甚哀哉!乃犯罪之大者也,皆因不明《易經》之本旨,而歸入異端邪妄之中矣。 (Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 34–5). |

| 16 | In the discovered copies of Yijing benzhi, a total of 44 hexagrams are reinterpreted. See Appendix A. |

| 17 | Several Jesuit Figurists’ Chinese manuscripts of the Yijing have been discovered, including Gu jin jing tian jian 古今敬天鑒 [The Mirror of Paying Homage to God in the Ancient Times and at Present], Yi yin 易引 [Introduction of Yi], Zhouyi yuan zhi tan 周易原旨探 [The Exploration of the Original Essence of Zhouyi], Yi yao 易鑰 [The Keys to the Yijing], Yi jing zong shuo gao 易經總說稿 [The Collection of All the Talks on Yijing], Da yi yuan yi nei pian 大易原義內篇 [Inner Chapter of the Original Meaning of the Great Yi], and Yi Gao 易稿 [Drafts of Yi]. In total, only 12 hexagrams, from Qian 乾 (The Creative) to Pi 否 (Standstill), were interpreted and elaborated. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | 惜吾不遇其盛時也。 (Lü 2013, vol. 2, p. 46). |

| 25 | 今反閉塞聖教之人,仁人之位當如此乎?(Lü 2013, vol. 2, p. 54). |

| 26 | 乃一聖子在于上下眾惡之中,乃替普世前古後今為世萬民受難受死,以補贖萬代世人之辜債。 (Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 44). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | Ibid., pp. 242–3. |

| 30 | All English translations of the biblical quotations in the book are taken from the King James Version unless otherwise specified. See (King James Bible 1996). |

| 31 | 陽剛中實,居險之中,行險而不失其信者也。(Cheng 2011, p. 163). |

| 32 | 上善若水。水善利萬物而不爭,處衆人之所惡,故幾於道。The English translation of the Daode jing is based on David Hinton’s version. See (Hinton 2015, p. 40). |

| 33 | 本旨一陽者,乃吾主也。因謙而降,受苦難而救人,是故曰〈勞謙〉。 (Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 375). |

| 34 | |

| 35 | |

| 36 | For the paradox of crucifixion, see (Behr 2006; Pius-Raymond 1954). |

| 37 | James Legge’s English translation is adopted in this particular paragraph in order to highlight the notion of “presenting offerings”. See (Legge 1963, p. 94). |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | 在噶瓦畧山上,用聖體聖血功勞,献于天主聖父也。(Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 411). |

| 41 | For the scriptural proof and theological significance for the priesthood of Christ, see (Cullmann 1963, pp. 83–9; Richardson 1958, pp. 225–9; Durrwell 1969, pp. 136–48). |

| 42 | According to the interlocking trigram principle, the lower interlocking trigram is formed by lines 2, 3 and 4 and the upper interlocking trigram by lines 3, 4 and 5. |

| 43 | Li Dingzuo 李鼎祚, Zhouyi jijie周易集解, 130. |

| 44 | 成言乎艮,乃吾主成七言,而救世之功在于艮山之上。(Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 44). |

| 45 | His interpretation exhibits some characteristics of numerical mysticism which will be discussed in more details in the following section. |

| 46 | 艮是東北方之卦也,東北在寅丑之間,丑為前歲之末,寅為後歲之初,則是萬物之所成終而所成始也。(Li 2000, p. 386). |

| 47 | |

| 48 | For the sacramental significance of the cross, see Richardson 1958, pp. 229–32; Durrwell 1969, pp. 186–201). |

| 49 | |

| 50 | |

| 51 | Ibid., p. 42. |

| 52 | |

| 53 | 代世人受補罪之刑,而不留人靈于地獄也。 (Lü 2013, vol. 2, p. 64) |

| 54 | 有意必有言,有言必有象,有象必有數。數立則象生,象生則言彰,言彰則意顯。The English translation of the text is based on Birdwhistell version. (Birdwhistell 1989, p. 76). |

| 55 | For Christ’s victory over death, see (Richardson 1958, pp. 190–214). |

| 56 | |

| 57 | For Christ’s bodily suffering, see (Guardini 1964, pp. 37–41; Chardon 1957). |

| 58 | 本旨渙汗者,乃吾主為罪人,而出流血汗也。以示傳教者,當效吾主需出其血汗也 […] 吾主之聖身乃為聖三之居,而忍為吾輩捨之。吾當以死還死,乃正位也。耶穌為師,我為其徒,不效耶穌,何以為之徒也?(Lü 2013, vol. 2, p. 115). |

| 59 | |

| 60 | Ibid., p. 32. |

| 61 | |

| 62 | For the symbolic significance of Christ’s wounds, see (Glotin 1979; Sava 1954). |

| 63 | 吾主路遇聖母,乃吾主聖意曰:「何為踵此污穢之塲,以甚吾之苦乎?惟有旋歸而已。」 […] 進上瓦略山,重苦在眼前,五內如刀攪崩裂母心肝。若非主恩佑,其命不保全。皆因世人罪,主母多艱。(Lü 2013, vol. 2, p. 5). |

| 64 | A note omitted in the New American Bible Revised Edition (NABRE) recalls this tradition: “In the liturgy this chapter is applied to the Blessed Virgin because of her constant and intimate association with Christ, the incarnate Wisdom.” For the Marian interpretation of Sirach 24 in Catholic tradition, see (Catta 1961, vol. 6, pp. 828–31, 860–1; Ratzinger 1983, pp. 25–7). |

| 65 | The English translation is based on Douay-Rheims’ version. |

| 66 | The Chinese translation is based on Poirot’s Guxin version. See (de Poirot 2014, vol. 6, p. 2150). |

| 67 | 主保人世間欽事貴,放效蒙恩引升天。(Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 125). |

| 68 | (Song 2018). |

| 69 | 兌為聖神,為聖愛,是吾喜言聖神之語。(Lü 2013, vol. 1, p. 43). |

| 70 | The original line from Zhongyong reads, 君子依乎中庸,遯世不見知而不悔,唯聖者能之。[The superior man accords with the course of the Mean. Though he may be all unknown, unregarded by the world, he feels no regret. It is only the sage who is able for this.] The English translation of The Doctrine of the Mean is based on James Legge’s version. See (Legge 1861, vol. 1, pp. 56–128). |

| 71 | |

| 72 | |

| 73 | |

| 74 | |

| 75 | For the influence of Li Guangdi on Bouvet’s Yijing-Figurism, see (von Collani 2007). |

评论